This year’s festival artist is none other than the world-renowned soprano and conductor Barbara Hannigan. Embodying music with an unparalleled dramatic sensibility and having performed nearly 100 world premieres, she is one of the most exciting artists in classical music. During Klarafestival, she conducts and sings Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra, performs an immersive scenic concert with the piano sisters Katia and Marielle Labèque, and brings along young artists from her mentorship program Equilibrium. Her artistic practice also inspired the theme for Klarafestival 2023: Become music.

For the opening of Klarafestival, you will not only conduct Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, but sing the soprano solo of the last movement as well. Conducting and singing Mahler at the same time: why put yourself through that?

Barbara Hannigan: I don't really think of it in that way, of putting myself through anything. I could say I put myself "in" it, in the music, in Mahler's world of sound, leading the orchestra through the narrative. We have, in this 4th symphony, a narrative which is by no means linear, but which is, rather, a series of images, philosophies, perspectives on society and social justice. The music is beyond time or place, and at the end, we have the final witness, the child, who (as Mahler wrote) should somehow offer the "key" to the piece.

In the 1990s, musicologist Christopher Small compared a classical music concert to attending mass, with the audience’s gaze directed forward, towards the altar on which the music of the “great, dead composer” is being interpreted by the awe-inspiring conductor. I have a sense you would disagree with his view?

BH: Even today, there are a lot of maestros, organisations and orchestras that still treat the conductor as the authoritative figure. This is not my interest. If we deny the fact that music is a collaborative exercise, we will eventually get lost. In any pieces where I am singing while on the podium, for example the final movement of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, we are at our most collaborative. I tell the orchestra, “It won't work for you to accompany me while I sing. This will create a delay and we will not be synchronized in either tempo or interpretation. You have to partner me in this." Sometimes the orchestra will lead, sometimes I will lead, and with every orchestra the equilibrium of this exchange is different.

Does this connect to a broader question for you, namely who is being given a voice, a stage?

BH: I am aware that when I am conducting, it does carry various meanings for the people in the concert hall; not least because they might have never seen a woman on the podium before. Gender aside, being in a place of authority means being in a place of responsibility. Another way to think of it: pressure is a privilege.

During Klarafestival, you will share the stage with several artists from your Equilibrium Young Artists program. Does your collaborative approach also affect the way you mentor promising musicians?

BH: Yes, absolutely. I think it’s important for young artists to understand that everyone, not only the star soloists, are leaders. We can develop this throughout our whole career. For EQ, I don’t hold auditions in the traditional sense. Instead, I organise an entire workshop day. The selected young artists work intensely with me, with Jackie Reardon who comes from the professional sports world, with their colleagues and a guest panelist. I observe their energy and the way they interact with each other: how do they share the room? What kind of questions do they ask? How do they listen? How do they work with the pianist? As for the singing, I ask them to perform for the entire room, in front of everyone, including their fellow candidates. This is scary to some, but in that way, it truly becomes a performance. And that’s of course what I’m looking for, performers.

You speak about your collaborative role as a conductor and a mentor, but how about your relationship to the composer?

BH: My relationship to the living composer has always been at the core of my career, since I gave my first world premiere at age 17. I’ve invested so much of my life and imagination into new repertoire, and to advocating for composers and their music. Over the years, I would say I've also become a very good editor, when the composer allows it. I am less interested in a composer dictating to me to the very last detail, exactly how to perform his or her piece. I love to work collaboratively, finding colours together, offering ideas and learning more about my instrument from an outside ear, which gives a lot of inspiration. In the past couple of years, working with John Zorn has been an extraordinary and life-changing experience, also with composer and arranger Bill Elliott with whom I've worked on tailor-made arrangements of Gershwin and Weill as well as his own music, and with David Chalmin, with whom I feel free to offer and exchange a lot of improvised material and ideas upon which he then expands.

To quote Christopher Small once more: what about “the great, dead composer”? What about Mahler?

BH: Well, sometimes it feels that even the relationship with the dead composer can be a collaborative exchange. Maybe all those years working with living composers has helped me to have a dialogue with the dead ones... Every time I open a score, old or new, there are new layers to be discovered. Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, for example, seems to be about the divide between the rich and the poor. Between the "haves" and the "have-nots". The last movement is called The Heavenly Life. It is a song, in which a child describes her vision of Heaven, where not only the good, but also the rich people and the violent people are present. She is astounded to be surrounded by so much abundance. I find it heartbreaking.

How do you perceive the role of the audience during a performance?

BH: I believe audiences aren’t just listening, but are actively contributing to a performance. They are bringing their energy and their experience to the room. ‘What is the meaning of this piece?’, someone once asked me. "The meaning" of a piece does not exist in a concrete way. Each audience member walks away with a different experience, just as every family member has a different experience of their family.

What about the audience member who sits completely still, without conveying any emotion or reaction. Is that person participating as well, according to you?

BH: Definitely. Of course it's easy to notice and appreciate extroverted reactions from the audience. Over time, I’ve come to understand that some audience members are in a state of deep concentration. Their listening is directed inward and this kind of presence contributes a lot to a performance. Sometimes there are audience members who I can see, at the end, do not applaud, but then they come backstage afterwards to thank us.

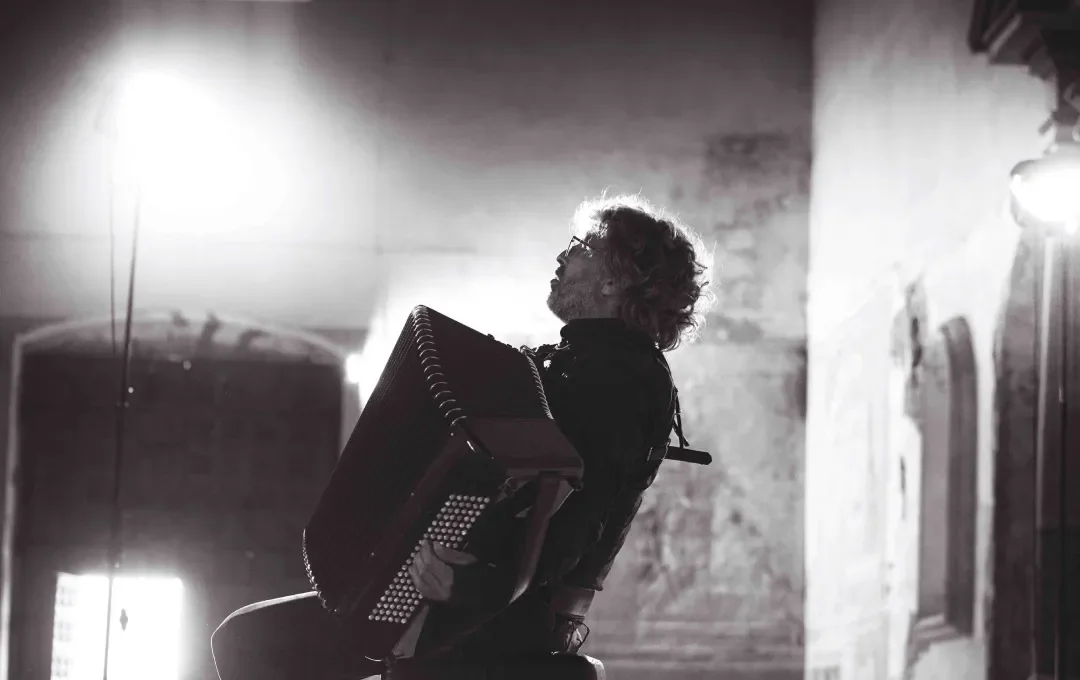

interview by Lalina Goddard, image © Marco Borggreve

come to the concerts with Barbara Hannigan

-

10.03 Bozar - London Symphony Orchestra & Barbara Hannigan

-

16.03 Flagey - Barbara Hannigan, Equilibrium Young Artists & Ludwig Orchestra

-

19.03 Bozar - Barbara Hannigan feat. Katia & Marielle Labèque

Want to know more about Barbara Hannigan and her artistic vision? Make sure to reserve your seat for the documentary I'm a creative animal on 17.03 in collaboration with Bozar Cinema.