interview with koen plaetinck

it's easier to understand baguettes flying through the window than the horrors of war

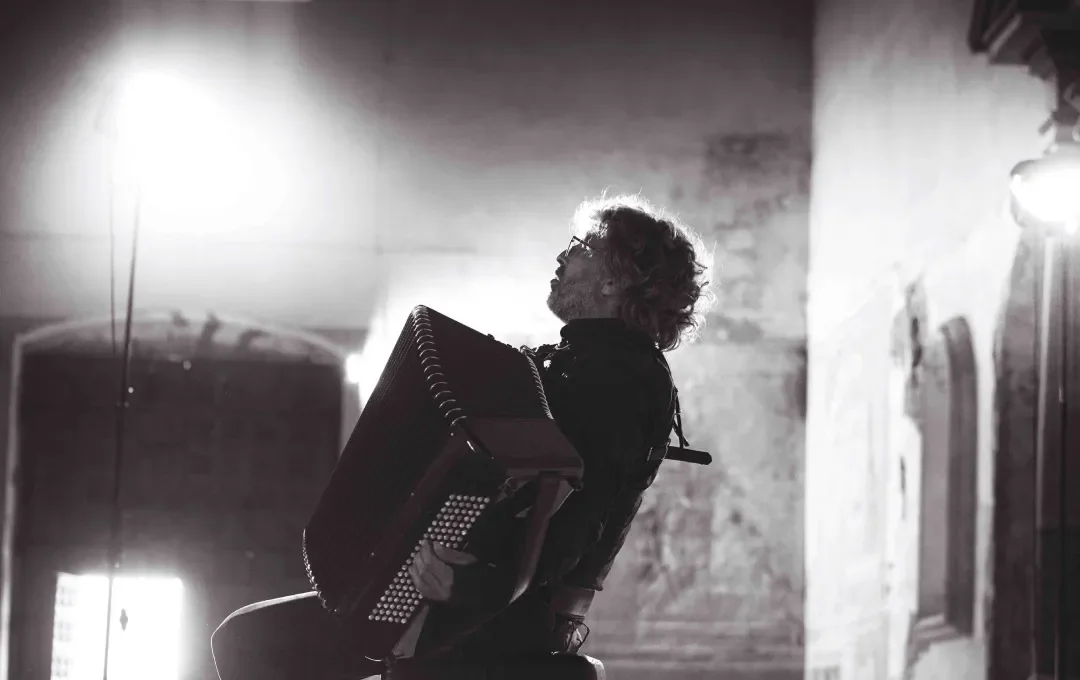

Making music without compromise. The amalgamation of authenticity and innovation. Beauty and creativity as the sole objective. Musical polymaths Wim Van Hasselt and Koen Plaetinck – the former trained as a trumpet player, the latter as percussionist – present with their brand-new duo ART’uur a counterbalance to the fast-moving, sometimes superficial daily tasks that typify the day-to-day life of the professional musician. They go passionately in search of depth and, in doing so, attempt to bring together all forms of art. Their first project, Imaginary Mirror, would have premiered at Klarafestival 2020. A conversation with Koen Plaetinck.

Mien Bogaert: Where did you meet Wim Van Hasselt and how did you start to work together?

Koen Plaetinck: Wim is someone I once studied alongside, a good friend and even a kindred spirit. A while back, we ran into each other again as soloists on a recording of Grunelius’ Chant d’Automne (for Flügelhorn, timpani and string orchestra) with the Budapest Festival Orchestra. Later on, Wim asked me to play on a couple of pieces for his next CD on Channel Classics. I suggested we do something a little more profound, something beyond the fleeting, more coincidental encounters. That was very straightforward: we didn’t want to do anything we were familiar with or that simply came along our path. We made the radical decision to use new compositions. One of the first composers we contacted was Markus Stockhausen, the son of Karlheinz Stockhausen. He has actually taken his own radical course and his music is the polar opposite of what his father stood for. In Markus’ music, which he calls ‘intuitive improvisation’, we see the beauty of music rather than the theory of music. After all, we have come to know many contemporary composers as highly-educated academic identities, concerned with concepts other than pure, simple beauty.

Mien Bogaert: How did the title of Imaginary Mirror come about?

Koen Plaetinck: We liked Markus’ music, but that doesn’t make a performance. There is a huge tendency towards dramaturgy at present. In search of a theoretical foundation, we arrived at surrealism: the philosophical school of the inter-war years. Surrealism is an extended reality, created in order to be able to process the horrors of the First World War. It’s easier to understand a Magritte painting in which baguettes fly through windows than what happened in ’14-‘18. The thing that fascinated us about surrealism, apart from its reason for existence – to enable human processing – was its aesthetic side and the combination of various disciplines. The title Imaginary Mirror was inspired by the painting Le Faux Miroir by René Magritte. He suggests that when one looks into a mirror, the mirror image one sees is always an interpretation. Therefore, the mirror image is always ‘false’ in some way. All the composers we engaged took inspiration from that theme.

Mien Bogaert: As well as new compositions you’re playing an arrangement of Spiegel im Spiegel.

Koen Plaetinck: That’s right. The label, Channel Classics, suggested we include an existing piece, for example Spiegel im Spiegel by Arvo Pärt. As we are personally in contact with this composer and he is incredibly committed to his music, we gave the piece a central place. I made the arrangement; he called me and checked the overtones on his piano over the phone. Phenomenal! Arvo Pärt is 84 years old… The arrangement of Spiegel im Spiegel functions in our concert as a mirror for the new compositions we play before and after it. We were always looking for parallels or contrasts. Florian Magnus Maier – a death metal guitarist with a classical education who composes within that tradition – is, for example, the perfect ‘mirror image’ of David Van Bouwel – a keyboard player and organist who writes the most progressive electronic music. Bart Cartier and Markus Stockhausen both work with the pure sound of our instruments and make use of the language they have studied: jazz. The former composed a piece for marimba and bugle, the latter a piece for vibraphone and bugle. Two other composers, Nicole Lizée and Daniel Wohl, come from the ‘Indie Classical’ angle. However, Daniel Wohl uses the sound as a point of departure while Nicole Lizée has an intrinsically storytelling, almost visual approach. She also provides the visuals to accompany her composition which deal with surrealism in a very literal sense.

Mien Bogaert: And then there is Sacred Places III by Wim Henderickx, a composition based on 16th-century shamanic singing. Isn’t the use of such Orientalist elements problematic these days?

Koen Plaetinck: At the end of the series of lectures Leonard Bernstein gave in Harvard in 1973 (The Unanswered Question), he made the case for ‘carefully selected eclecticism’. You do not have to build everything from the ground up: new things arise from the combination of existing things. Wim Henderickx is a great admirer of eastern religions, Florian Magnus Maier takes inspiration from Balkan folk music, Bart Quartier has written a piece about Japan, and so on. I think, as Bernstein said, that carefully selected eclecticism is the road we must follow in our modern, global world, where everything is simultaneously very far away and very nearby. That also coincides with the philosophy of surrealism: creating a new reality by placing familiar things in a different context. Or, in the case of Wim Henderickx, by combining 16th-century shamanic singing with the tones of a trumpet with a fourth valve.

Mien Bogaert: There are quite a lot of electronics involved in your new show. To what extent do these electronics restrict or expand your scope?

Koen Plaetinck: They expand it, without a doubt. We could play our music without electronics but then we’d need ten instrumentalists on stage instead of two. Electronics broaden your possibilities to a phenomenal extent: in Wim Henderickx’s composition we test the expression of our notes against the underlying shamanic songs which are then processed again live: more and less, higher and lower, louder and quieter. For us as a duo, it feels like we’ve got a third musician among us. The trumpet can also think in a much more harmonic way: at one particular moment Wim Van Hasselt plays a polyphonic chorus.

Mien Bogaert: Why did you – or the composers – decide to work with visuals too?

Koen Plaetinck: In a concert you communicate emotions. As a musician you are starting a conversation with the audience. That is often one-way traffic, but sometimes you get to the point where an actual dialogue develops. In the times we live in, however, the visual aspect is equally invaluable. Images can often convey feelings even better than sound. A number of the composers we have used were already working with visual artists anyway. What they write often goes hand-in-hand with certain images, so it seemed worthwhile to us to bring visuals into it. However, there is also a third component in our performance in addition to the sound and the image that increases the dialogue with the audience even further. Almost everyone has a smartphone these days. Rather than seeing these devices as disruptive elements that should be switched off and banished, we had software developed that localises all the smartphones in the venue. For us, every smartphone is a speaker that we can operate. We transmit signals from the stage to the smartphones in real time, and the smartphones can also send signals back to the stage.

Mien Bogaert: As a percussionist, you specialise in historic performance practice in your daily existence. You collect historic instruments and play in a number of baroque ensembles. How do you reconcile this with the contemporary music the two of you are playing?

Koen Plaetinck: For me, there’s hardly any difference between old and new music. Jos van Immerseel once said that in historic performance practice, you’re playing every piece as if it was the first time – with the information on how it was then in that era. You perform Bach’s Hohe Messe as if the ink is still wet on the paper. That might seem to lack nuance, but there’s a lot of truth in it. When I’m given Wim Hendrickx’s score (written for frame drum, hand drum and shamanic drum) then I actually ask myself the same questions as I do with Bach’s Hohe Messe: what are the instruments that Wim Hendrickx has himself at his disposal? How did he play them? What did he mean with that notation process? Of course, knowledge of the various instruments and mastery of the different playing techniques are essential: that’s hard work. The advantage of composers who are still alive is that you can still go and ask them yourself. However, the thought process is exactly the same for me.