interview shuang zou and wim henderickx

On March 13, Muziektheater Transparant opens the first ever online edition of Klarafestival.

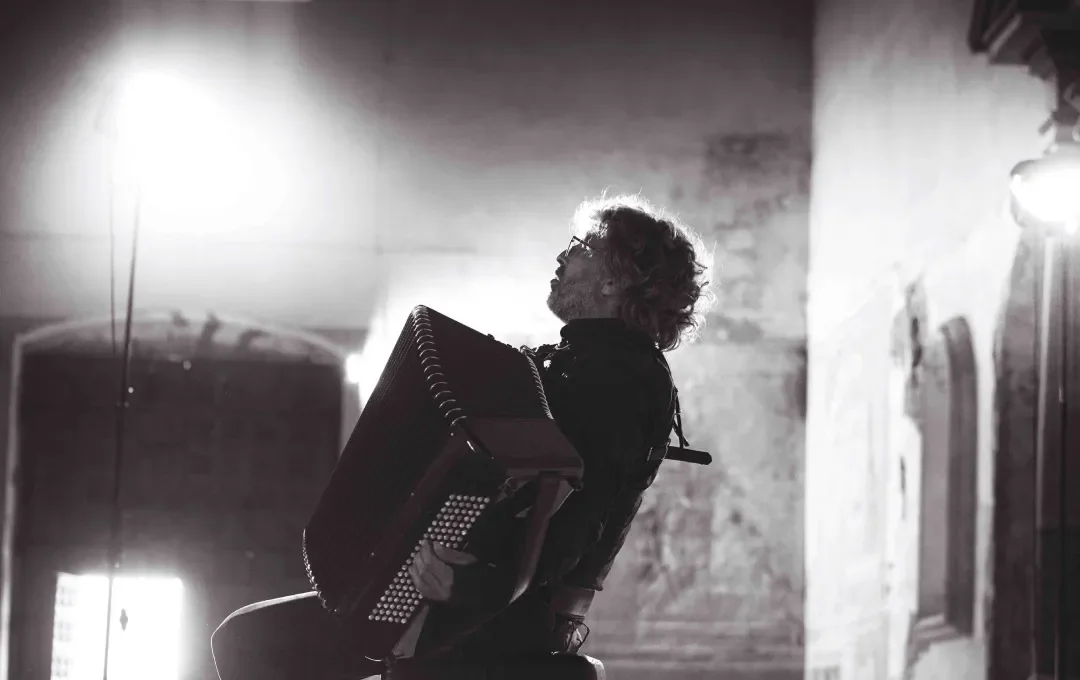

Chinese theatre and opera director Shuang Zou and house composer Wim Henderickx create a unique interplay of Handel’s rarely-performed Neun deutsche Arien in combination with new, contemporary compositions. The Ghent Baroque orchestra B’Rock and Belgian soprano Ilse Eerens will perform the music.

dependent on nature

Klarafestival 2021 draws inspiration from the sign above the lost property office at Wuppertal station in Germany: ‘es ist noch nicht alles verloren’ (‘all is not lost’). It also focuses on the relationship between man and his habitat. The image of man as a rational being, separate from nature, has been dealt a blow by coronavirus. “We are still dependent on nature, and music can restore or strengthen that connection.”

Hendrik Storme (currently artistic director at deSingel, formerly of B’Rock and Klarafestival) asked Wim Henderickx a few years ago to write a contemporary addition to Handel’s Neun deutsche Arien. This became the basis for the production of Songs of Nature. The international production team was assembled last year and includes Chinese director Shuang Zou, Italian film maker Marco Devetak and Australian set designer Dan Porta. They all rehearsed in Borgerhout, Transparant’s home base, in March 2020. A week later, the country entered lockdown. Joost Fonteyne, the current artistic director at Klarafestival, recently reached a decision with BOZAR to open the digital Klarafestival 2021 with Songs of Nature.

Zoom

Today, February 12 2021, we have a Zoom call with Shuang, joining us from Beijing, and Wim from Antwerp. It is the first day of the Year of the Ox, she tells us when we introduce ourselves. “We celebrated the Chinese New Year yesterday. We celebrate it the way you celebrate Christmas, with the whole family and a countdown to midnight.” She explains that things are now more or less back to normal in China, apart from not being able enter or leave the capital without a coronavirus test. International travel is also prohibited, which has complicated the Songs of Nature production process considerably.

Shuang: “I can’t get a visa as the embassies are closed. I have a green card for the UK, but not for Europe. The opposite is also true: foreigners are not allowed to enter China. So these are complicated times in our line of work. The whole online thing makes me nervous. Directing this piece on Zoom will be a new experience for me. Unfortunately, I can’t attend the general rehearsals or the premiere. I had a frightening dream yesterday: none of the musicians knew me because I was a virtual person,” she laughs heartily. “I noticed that you are still rehearsing at midnight sometimes,” says Wim in astonishment. “That’s right,” replies Shuang, “Beijing is seven hours ahead of Belgium, so if rehearsals begin at 10 am, it’s 5 pm over here. In Australia, you can add another two hours, so it can get quite late…”

God’s voice versus industrialisatie

The practical organisation illustrates how complex the current situation is, in global terms, but they are both surprised at how current the production still is despite all the twists and turns the project has been through so far. Shuang: “On January 18 2019, I was walking through the streets of Brussels when I came across a group of youngsters demonstrating for climate action. Although I’d heard about this on radio and TV, the event really affected me. I wanted to use them for this piece.” She wrote a premise for the soprano who was to be the main character in this ‘one woman show’: I imagined that the woman who organised this youth demonstration was a teacher or an activist. At one point she rushes inside to shelter from the rain. She might go back to the street after ten minutes, but she is intrigued by the room she now finds herself in. It’s quiet and peaceful, despite the litter scattered around. She discovers hidden plants in the room and in the abandoned refrigerator. In the next scene, she switches roles and behaves as if she is the last person to have lived in that space. This person cares for the plants and grows a garden. The fridge, which symbolises our industrialised world with its surplus of frozen food and mankind’s struggle against time with the likes of Botox, sends her messages. They are initially fun and light-hearted, but the woman becomes entangled by her own doing and it all ends in horror: she is swallowed by the void. A reference to the Buddha’s ‘the ultimate nature is emptiness’. “We haven’t worked out exactly how we will do that yet,” laughs Shuang. As well as the refrigerator, we see a screen on the stage, a window offering a glimpse of both the world outside and the inner life of the woman. The window acts predictively and leaves many questions unanswered in the end. “Call it God’s voice,” the director explains. At the end of the piece, which lasts just over an hour, we do not know how long the woman has actually been in the space. It could be weeks, years, a lifetime. Shuang: “There is a lot of humanity and vitality in Handel’s music. That’s why I wanted the protagonist to go on a psychological journey that results in new insights. Like life itself. We will all meet the same end, but we gain insights along the way.”

a different angle

Shuang wanted to show this humanity in the everyday setting of a room in a house with a fridge and a window. “I remember the first sketches you sent me,” reveals Wim. “I remember finding it really strange at first. But the more we worked on it, the more convinced I became that it was the contrast between this everyday setting and my music that would appeal to the audience. It’s that different angle that I find so interesting in the case of Shuang; it makes her artistic interpretations radically different from those of the Western directors I know.”

Dialogue

Shuang: “Wim is very versatile in his musical styles. He knew so much about the music of the Far East; more than me. He went to Nepal, and discovered Indian Sufi music. When I saw Revelations at Klarafestival 2017 I was amazed at how Eastern this music sounded. I determined that I would find out more about my own roots. A year later, I went to Nepal myself and discovered Buddhism. When we met again in Belgium he persuaded me to juxtapose Handel’s Western religious background with Eastern Buddhist culture.”

four seasons

Wim: “For me, nature is linked to spirituality. When I’m out walking, or meditating, I feel an internal connection. It brings me peace. I wanted to integrate this spirituality. When Hendrik asked me to write music for the songs of Handel, to be honest I didn’t know the music well enough; it’s one of his last pieces. The link between Renaissance music and contemporary is sometimes more straightforward, but how do you do that with Baroque? With Shuang’s input, it soon became clear to me that I didn’t want to comment on Handel's songs as a whole. It didn’t feel right. It wasn't respectful, to either Handel or me. So when we divided the songs into four sections, I wrote four compositions as a complement to the whole thing rather than individual songs. These are the moments when the protagonist goes on her inner journey, searches for the transcendental, perhaps even meditates. This could be in a peaceful way, as we might traditionally interpret the concept of spirituality, but it could equally be coupled with fire, passion or intense emotions.” “I have immersed myself in Baroque music again, and the music of B’Rock. I wanted to return to that rhythmic intensity, and to the ornaments in the music. There is so much freedom in this kind of music. I’ve added those elements to my own music too. It hasn’t turned entirely contemporary; I think you can sense the Baroque vibe. Call it my ‘four seasons’: Sweet silence (summer), Into the darkness (autumn), Into the light (spring) and Joy (winter). The titles of the pieces are taken almost literally from the poems that Handel set to music. Working with different instruments also inspires me. The musicians in B’Rock have a specific timbre, which intrigues me as a composer. It makes you use vibrato differently; you create different accents. There are also limitations: for example, the 18th-century traverso doesn’t offer all the possibilities of the modern flute.”

Common ground

In closing, Wim Henderickx wonders how the production will go down with an online audience. “Can we go as deep as we would in a live performance? When I think of what I hope the audience will experience, a single word comes to mind: introspection.” Shuang hopes that this piece will help to create a kind of common ground with which the audience can identify. “We have built the story around an everywoman character with regard to colour, cultural background and religion. So we created a room into which anyone might walk, and that shows how similar we all appear. We had the idea before the pandemic, but it’s all the more relevant now.”